Um, hang on...what?!

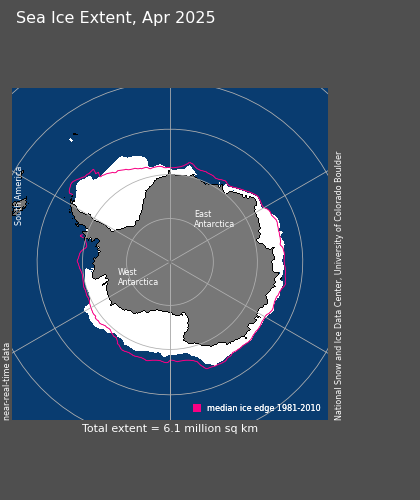

Didn't we spend last week discussing how Arctic sea ice is in DECLINE? Surely the Antarctic is warming up too, and if so, should be losing sea ice in the same way? This seems entirely contradictory and confusing...But fear not! While the trend in sea ice extent has been referred to as a 'puzzle' and 'enigma' in recent news reports, a number of possible explanations have been presented.

While counter-intuitive, it's important to realise that the increase in sea ice extent does not mean the Antarctic is cooling. Within the Southern Ocean, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is increasing in temperature more quickly than the global average, and temperatures on the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula have risen by almost 3°C within the last 50 years (NERC-BAS, 2014). But if the region is undergoing warming, how is it that more sea ice is forming?

The first thing to remember is that we are indeed talking about sea ice. This is simply - as the name suggests - ice formed through the freezing of sea water. In other words, reports you've heard about melting glaciers and collapsing ice shelves on Antarctica are correct - these are referring to land ice.

|

| Sea ice is formed through the freezing of sea water. It therefore does not contribute to sea level change upon melting. Source: www.nsidc.org |

Zhang (2007) suggests that a strengthening of ocean stratification may be responsible for the observed increase in sea ice production. Models which incorporate a rise in air temperature show decreasing levels of ice formation, which in turn lead to decreased salinity levels in surface waters (since salts are rejected during ice formation) (Zhang, 2007). A decrease in salinity reduces the density of the water, and heightens the thermohaline stratification of the water column. This lessens convective overturning and the upward heat flux, allowing for greater sea ice formation and reduced melt (Zhang, 2007). Other factors which decrease the salinity of surface waters - for example, increased precipitation or freshwater run-off from melting land ice - could bring about the same result (Earthsky, 2014). Freshwater also has a higher freezing point than salt water, further increasing ice production.

It should be mentioned at this point that sea ice increase is not observed everywhere in the Antarctic, with sea ice decline seen in some regions, for example the Bellingshausen and Amundsen seas (IPCC, 2013). However, the overall net change is positive, with the large amount of ice produced in the Ross Sea outweighing the loss elsewhere (IPCC, 2013). It is thought that changes in atmospheric and ocean circulation could be responsible for these effects. For example, strengthening winds can push ice away from the continent, creating coastal polynyas (ice-free areas) where more ice can then form. The exact cause of these changes is unknown, though they could be part of natural climate variability (NASA, 2014). Turner et al. (2009) suggest that loss of stratospheric ozone could be responsible. In their model, decreasing ozone led to the deepening of a low pressure system called the Amundsen Sea Low, which gave increased ice production in the Ross Sea (Turner et al., 2009).

|

| A penguin having a little trouble in the strengthening winds... Source: www.gdargaud.net |

Increased snowfall is another explanation for the observed changes. Firstly, the weight of snow that falls directly onto the sea ice can force it beneath the ocean surface. This means sea water floods the ice, increasing its thickness when it subsequently freezes and produces 'snow ice' (IPCC, 2013). Secondly, it has been suggested that increased snowfall on the Antarctic landmass, while increasing ice thickness at the centre of the ice sheet, leads to loss of ice (in the form of ice bergs) at its margins (CBC News, 2014). A greater number of ice bergs leads to reduction in ocean movement, facilitating sea ice production (CBC News, 2014).

This is not an exhaustive account of the theories that have been put forward to explain the increase in sea ice around Antarctica. Indeed, it is likely to be a combination of these suggestions, or perhaps another mechanism entirely. Furthermore, owing to the remote location of this region, and a lack of historical data (satellite observations only began in 1979), there is still plenty to learn about this phenomenon. The observed increase in sea ice was not predicted by climate models, and it is possible that natural climate variability is responsible for the changes seen (IPCC, 2007; Turner et al., 2009) . This makes sea ice increase a contentious topic, as demonstrated by this (timely!) debate on Tuesday's Newsnight (see 33.48 onwards).

No comments:

Post a Comment